Download the complete PDF here or check out the point of care tools and the more comprehensive GECKO Deep dive. (Updated Dec 2025)

What is Lynch syndrome?

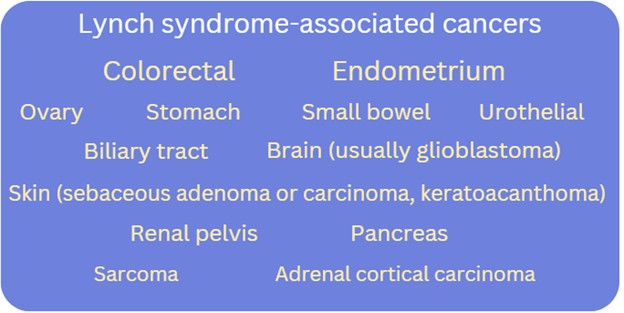

Lynch syndrome (LS), previously known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), is the most common form of hereditary colorectal cancer (CRC) and endometrial cancer (EC), affecting at least 1 in 279 individuals.1,2,3. LS is autosomal dominant. In addition to an increased lifetime risk for colorectal and endometrial cancers, there can be an increased risk for malignancies in the stomach, small bowel, brain, skin and more. Cancer risks and age of onset depend on which LS-associated gene is identified to have a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in the individual/family.

What are the Lynch syndrome-associated cancer risks?

Check out this GECKO point of care tool for gene-associated cancer risks.

How is genetic testing done?

Genetic testing is generally performed on a blood sample and involves a multigene panel, where more than one gene is analyzed at the same time. In the case of Lynch syndrome (LS), at a minimum, the 5 LS-associated genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM) are included. Depending on availability and family history, additional genes associated with other hereditary cancer syndromes may be included on the gene panel.

Somatic (tumour) versus germline (blood) testing. What does this mean?

In cancer, somatic testing refers to genetic testing of the tumour. This is done to inform treatment, not carrier status. A pathogenic variant present in a tumour does not confirm a hereditary predisposition in the individual. If no pathogenic variant is detected, this does not rule out a hereditary predisposition in the individual and germline genetic testing may still be indicated.

Germline testing, typically performed on a blood sample, refers to genetic testing to identify inherited pathogenic variants - those that were present at conception in the egg or sperm.

- Germline pathogenic variants are expected to be present in every tissue. These are inherited and can be passed on to offspring.

- Somatic pathogenic variants are isolated to a particular tissue (excluding eggs and sperm) and are not passed on to offspring. These are acquired and sporadic.

In the metastatic setting, tumour biomarkers such as KRAS and NRAS, and BRAF mutations are tested to determine whether targeted therapies are indicated. These biomarkers mediate signalling pathways driving growth and proliferation of tumour cells, so therapies directed against these targets can arrest or slow tumour growth.5

Who should be offered genetic testing/assessment?

Check out the bottom line for who should be considered for a genetic assessment or the GECKO deep dive for more information.

What do the genetic test results mean?

For more information on genomic testing and results see our point of care tool. Most provincial genomic laboratories and clinics will have board-certified genetic counsellors available to answer your questions about genetic test results and are happy to take your calls.

Affected individuals (have/had cancer diagnosis)

Positive result: A pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) variant in a cancer predisposition gene was identified. If the gene is associated with the person’s cancer diagnosis, this explains their cancer. Results may be used by oncology to inform treatment and/or surveillance plan and may allow for access to new effective therapies. The individual is likely at higher risk for subsequent cancer diagnoses. Additional screening and surveillance for other cancers may be indicated. First degree relatives (parents, siblings, offspring) have a 50% chance to inherit this gene variant and to also be at risk. Relatives can have genetic testing for this familial variant.

Negative/uninformative result: No variants of clinical significance were identified in any of the genes on the cancer panel. Given the comprehensiveness of cancer gene panels, a negative result significantly reduces the likelihood of a hereditary cancer condition in the person tested. Depending on the family history, other relatives may still be eligible for genetic testing. Screening and surveillance recommendations for the individual and their relatives will be based on personal and family history.

Variant of uncertain significance (VUS): A variant in a gene was identified but its significance is not yet known. The laboratory cannot confidently determine if the gene variant identified is pathogenic or benign, as available evidence is insufficient or conflicting. This result is reassuring as pathogenic variants in high/moderate risk cancer genes have been ruled out, however a hereditary cancer condition cannot be completely excluded. A board-certified genetic counsellor or a geneticist can help to interpret the laboratory report. No changes to medical management are indicated. Family members are typically not offered genetic testing for a VUS. Clinics and laboratories differ in their re-contact protocols, but generally a patient would be encouraged to re-contact their genetics provider in 3-5 years for updates on re-classification of the VUS they carry. Re-classification of a VUS could mean the variant is now determined to be pathogenic or more often, benign.

Unaffected individuals (never had a cancer diagnosis)

Positive result: A P/LP variant in a cancer predisposition gene was identified.

The individual is at increased risk for cancers associated with the gene. Screening and medical management recommendations can be made based on the combination of genetic test result and family history. First degree relatives (parents, siblings, offspring) have a 50% chance to inherit this gene variant and to also be at risk. Relatives can have genetic testing for this familial variant.

Negative result:

True negative: The familial variant was not detected.

This is where a P/LP variant in a cancer predisposition gene has already been identified in a relative. Testing was solely to detect the presence or absence of the familial pathogenic variant. This individual is not at increased risk for cancer. Depending on the family history, population-based cancer screening is still recommended.

Uninformative: No variants of clinical significance were identified in any of the genes on the cancer panel.

Given the comprehensiveness of cancer gene panels, a negative result significantly reduces the likelihood of a hereditary cancer condition in the person tested, however without confirmation of a gene variant responsible for the family’s cancer, this is uninformative. Screening and surveillance recommendations for the individual and their relatives will be based on personal and family history. Depending on the family history, other relatives may still be eligible for genetic testing.

Variant of uncertain significance (VUS): A variant in a gene was identified, but its significance is not yet known. The laboratory cannot confidently determine if the gene variant identified is pathogenic or benign, as available evidence is insufficient or conflicting. A board-certified genetic counsellor or a geneticist can help to interpret the laboratory report. No changes to screening or medical management are indicated. Family members are typically not offered genetic testing for a VUS. Clinics and laboratories differ in their re-contact protocols, but generally a patient would be encouraged to re-contact their genetics provider in 2-5 years for updates on re-classification of the VUS they carry. Re-classification of a VUS could mean the variant is now determined to be pathogenic or benign.

NOTE: In some genes, when two P/LP variants are inherited, one from each parent, this can result in a serious clinical presentation with high cancer risk and childhood onset (e.g. PMS2/PMS2 results in constitutional mismatch repair deficiency which can result in child-onset cancers). If there is suspicion of a hereditary cancer predisposition in the partner of a carrier of a LS-gene P/LP variant or known consanguinity, consider genetic counselling for the couple.

A word about Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS): A VUS is a result that leaves ambiguity for a patient and, depending on a patient’s experience with cancer (personal and family), attitudes toward healthcare and education level, there may be an inappropriate expectation of increased monitoring based on the result.4 Discussions with healthcare practitioners are important in shaping a patient’s understanding of the result, managing uncertainty and setting expectations.10 It is also important to note that the rate of VUS is reported to be significantly higher in those of non-European ancestry (e.g. Hispanic, African, Asian and Pacific Islander). This has to do with the lack of diversity in clinical and research contexts and the under-representation of non-European groups in genomic databases that are used for interpretation by laboratories.9 The majority of VUSs in hereditary cancer risk genes will eventually be classified as benign.

What are the benefits and considerations of genetic testing?

Benefits:

- A positive result can explain why a person developed cancer and confirm a hereditary predisposition in the family

- Oncology may use the result to inform treatment

- Additional surveillance, medical and/or surgical recommendations may be suggested

- Clinical intervention for those with known hereditary cancer predispositions can improve outcomes12

- Relatives can have genetic testing for the familial variant

- At-risk relatives can be identified and other relatives without the familial variant can be reassured. Both can be given more accurate risk assessments1 and management plans

- Positive health behaviours can be reinforced1

Considerations:

- Some may experience psychological distress over:

- the increased risk to develop cancer

- the possibility of passing an increased cancer risk to offspring

- the uncertainty of a negative result or a variant of uncertain significance

- the uncertain likelihood of a cancer diagnosis, as not everyone with a genetic predisposition will develop cancer

- Family issues such as confidentiality concerns or estrangement may inhibit the transfer of information between relatives

- In Canada, the Genetic Non-Discrimination Act (GNA) became law in 2017. This law protects Canadians and their genomic information. Some key points of the law are that GNA prohibits:14

- Discrimination based on genomic characteristics

- Providers of goods and services (including insurance) from:

- requesting or requiring a genomic test

- requesting or requiring the disclosure of genomic test results either past or future

- Federally regulated employers from using genomic test results in decisions about hiring, firing, job assignments, or promotions

Gene-specific cancer surveillance and management recommendations

A multidisciplinary approach involving medical, surgical, and genetic specialties is the best approach to managing those with a hereditary cancer predisposition.1 Consider a referral to a genetics specialist if not already arranged to ensure the patient receives appropriate counselling regarding their hereditary condition. If your patient had genetic counselling several years ago, consider reaching out to your local genetics specialist by phone or eConsult to inquire about any updated screening recommendations, as they evolve over time.

For those currently under the care of oncology: the oncologist will likely recommend screening and surveillance related to the current cancer diagnosis. Because those with hereditary cancer predispositions often have increased lifetime risk for additional cancers, management of those risks may be appropriate after treatment of the current cancer or may be combined with treatment for a current cancer.

Check out this point of care tool or the more comprehensive GECKO deep dive for more on gene-specific surveillance and management recommendations.

Disclaimer:

· GECKO is an independent not-for-profit program that does not accept support from commercial or non-academic entities.

· GECKO aims to aid the practicing non-genetics clinician by providing informed resources regarding genetic/genomic conditions, services and technologies that have been developed in a rigorous and evidence-based manner with periodic updating. The content on the GECKO site is for educational purposes only. No resource should be used as a substitute for clinical judgement. GECKO assumes no responsibility or liability resulting from the use of information contained herein.

· All clinicians using this site are encouraged to consult local genetics clinics, medical geneticists, or specialists for clarification of questions that arise relating to specific patient problems.

· All patients should seek the advice of their own physician or other qualified clinician regarding any medical questions or conditions.

· External links are selected and reviewed at the time a page is published. However, GECKO is not responsible for the content of external websites. The inclusion of a link to an external website from GECKO should not be understood to be an endorsement of that website or the site’s owners (or their products/services).

· We strive to provide accurate, timely, unbiased, and up-to-date information on this site, and make every attempt to ensure the integrity of the site. However, it is possible that the information contained here may contain inaccuracies or errors for which neither GECKO nor its funding agencies assume responsibility.