Download the comprehensive GECKO Deep dive, the quick reference GECKO on the run, and/or the point of care tools.

Updated Dec 2025

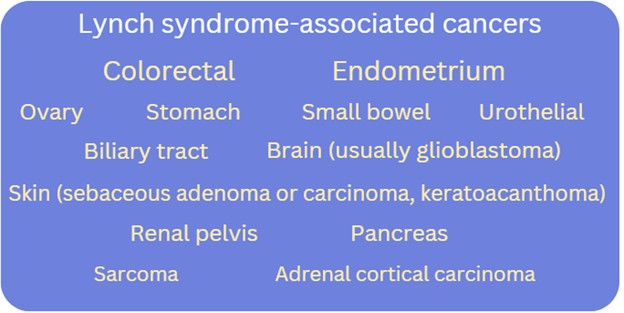

Bottom line: Lynch syndrome (LS) is a common (1/279) autosomal dominant hereditary cancer predisposition syndrome. LS is associated with an increased lifetime risk for colorectal (CRC) and endometrial (EC) cancer in addition to cancers of the ovary, stomach, small bowel, pancreas, biliary tract, urothelial tissue and renal pelvis, brain (i.e. glioblastoma), and skin (i.e. sebaceous adenoma or carcinoma, keratoacanthomas). The actual cancer risk depends upon which LS-associated gene contains a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant. Genetic assessment should be considered for those with a:

Primary care practitioners have a role in identifying those who could benefit from a genetic assessment, coordinating high-risk screening (e.g. annual colonoscopy), and referring for specialist consultation (e.g. gynecology, gastroenterology) for consideration of risk-reducing management and screening recommendations. |

Jump to a section

- What is Lynch syndrome?

- What causes Lynch syndrome?

- What are the Lynch syndrome-associated cancer risks?

- How is genetic testing done?

- Who should be offered genetic testing/assessment?

- What do the genetic test results mean?

- What are the benefits and considerations of genetic testing?

- Gene-specific cancer surveillance and management recommendations

- References

What is Lynch syndrome?

Lynch syndrome (LS), previously known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), is the most common form of hereditary colorectal cancer (CRC) and endometrial cancer (EC), affecting at least 1 in 279 individuals.1,2,3. LS is autosomal dominant. In addition to an increased lifetime risk for colorectal and endometrial cancers, there can be an increased risk for malignancies in the stomach, small bowel, brain, skin and more. Cancer risks and age of onset depend on which LS-associated gene is identified to have a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in the individual/family.

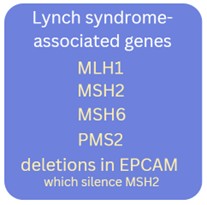

What causes Lynch syndrome?

Lynch syndrome results from an inherited genetic variant (pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant) in 1 of 4 genes: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2, or deletions in the EPCAM gene which alter the normal function of the MSH2 gene. The first four genes are mismatch repair (MMR) genes, which have roles in repairing base-to-base mismatches during cell division/DNA replication. Loss of function of the MMR pathway in a cell can result in accumulation of replication errors which can interfere with the integrity of the genome.4,5

What are the Lynch syndrome-associated cancer risks?

Exact cancer risks may also be influenced by family history, geographical location and other risk factors.1

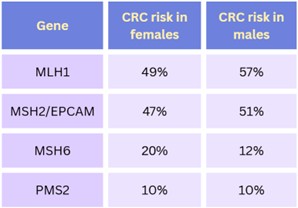

Table 1. Colorectal cancer (CRC) risks for those who are carriers of a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in a Lynch syndrome-associated gene.1 The general population risk for CRC is about 6% over one’s lifetime.6

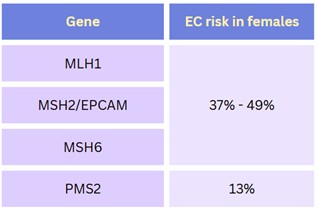

Table 2. Endometrial cancer (EC) risks for those assigned female at birth who are carriers of a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in a Lynch syndrome-associated gene.1 The general population lifetime risk for EC is about 3%.7

How is genetic testing done?

Genetic testing is generally performed on a blood sample and involves a multigene panel, where more than one gene is analyzed at the same time. In the case of Lynch syndrome (LS), at a minimum, the 5 LS-associated genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM) are included. Depending on availability and family history, additional genes associated with other hereditary cancer syndromes may be included on the gene panel.

Somatic (tumour) versus germline (blood) testing. What does this mean?

In cancer, somatic testing refers to genetic testing of the tumour. This is done to inform treatment, not carrier status. A pathogenic variant present in a tumour does not confirm a hereditary predisposition in the individual. If no pathogenic variant is detected, this does not rule out a hereditary predisposition in the individual and germline genetic testing may still be indicated.

Germline testing, typically performed on a blood sample, refers to genetic testing to identify inherited pathogenic variants - those that were present at conception in the egg or sperm.

- Germline pathogenic variants are expected to be present in every tissue. These are inherited and can be passed on to offspring.

- Somatic pathogenic variants are isolated to a particular tissue (excluding eggs and sperm) and are not passed on to offspring. These are acquired and sporadic.

In the metastatic setting, tumour biomarkers such as KRAS and NRAS, and BRAF mutations are tested to determine whether targeted therapies are indicated. These biomarkers mediate signalling pathways driving growth and proliferation of tumour cells, so therapies directed against these targets can arrest or slow tumour growth.5

Who should be offered genetic testing/assessment?

In general, the best and most informative person in a family in whom to begin genetic testing and assessment is the person most likely to have the genetic condition. This is usually the youngest person diagnosed with a Lynch syndrome (LS)-associated cancer.

In general, the best and most informative person in a family in whom to begin genetic testing and assessment is the person most likely to have the genetic condition. This is usually the youngest person diagnosed with a Lynch syndrome (LS)-associated cancer.

Familial Variant Testing

Once a pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) variant has been identified in a family, other relatives are eligible to have genetic testing for that variant, leading to more accurate risk assessments, screening and management recommendations.

Unaffected individuals who are considering testing should be offered genetic counselling so that an informed decision is made about whether and when to pursue predisposition testing*. First degree relatives of those who carry a P/LP variant in a LS-associated gene have a 50% chance to carry the same P/LP variant and to be at increased risk for the gene-associated cancers, and a 50% chance to not be a carrier. A negative result is reassuring but does not eliminate all cancer risk. Individuals would still be advised to follow population-based cancer screening.

Genetic counsellors can help facilitate communication of results among relatives by providing/sending family letters with de-identified information, after ensuring appropriate consent to share genetic information is obtained and documented. Primary care practitioners can play a key role in cascade testing of hereditary conditions by discussing the benefits of sharing results of genetic testing, and by making referrals. A recent meta-analysis reported that about 1/3 of relatives were not informed about their risk to carry a P/LP variant and, of those that were informed, less than half went on to have genetic testing. Some barriers to disclosure of results to relatives include:8

- not being in close contact with relatives

- fear of causing relatives distress or anxiety, or finding the topic too distressing to bring up

- considering relatives to be either too old or too young to learn about the familial condition

- not understanding why sharing information is important

- feeling that genetic information is too personal to share

Both genetics and primary care practitioners are well positioned to provide support and education to overcome these barriers.

*Predisposition testing is performed on an unaffected individual, where a positive result confers an increased risk to develop one or more conditions e.g. increased lifetime risk for colorectal cancer. Predictive testing is performed on an unaffected individual where a positive result means the individual will develop the genetic condition e.g. Huntington disease.

Clinical Criteria

There are several methods, such as the Amsterdam Criteria, to determine whether an individual could benefit from a genetic assessment.

Amsterdam Criteria

Consider referral for a genetic assessment when an individual has a diagnosis of a LS-associated cancer AND two relatives with an LS-associated cancer. The following family criteria should also be met:

- One relative should be a first-degree relative of the other two (e.g. parent and child, siblings)

- At least two successive generations should be affected

- At least one LS-associated cancer should have been diagnosed before age 50 years

Some genetics clinics will use risk calculators such as PREMM 5 to determine the chance a P/LP variant in an MMR gene is present, and offer genetic testing if the likelihood is greater than or equal to a certain percentage (commonly >5%). In Canada, there is no current consensus on eligibility criteria and these vary by province, although all provinces will assess an individual who meets Amsterdam Criteria.1 Check with your local genetics clinic/hereditary cancer program about their referral criteria.

In general, in addition to those who meet Amsterdam criteria, genetic assessment should be considered for those with a:1,2

- Family history of a known pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in a LS-associated gene (MLH1, MSH6, MSH2, PMS2, EPCAM). All but EPCAM are also known as mismatch repair (MMR) genes.

- Personal history of LS-associated cancer (i.e. CRC, EC or other cancer listed above) diagnosed at <50 years

- Personal history of CRC or EC at any age and a family history of LS-associated cancer, with at least one cancer diagnosed <50 years (the individuals diagnosed with cancer should be related to each other)

- Personal history of CRC or EC and two or more relatives with LS-associated cancers, regardless of age

- Personal history of multiple primary LS-associated cancers

- Personal history of a LS-associated tumour where immunohistochemical (IHC) staining shows deficient mismatch repair (MMR) gene expression, consistent with LS [see below for more]

- Probability of carrying a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in a LS-associated gene estimated to be >5%, calculated by a validated risk calculator e.g. PREMM5

If relative(s) affected with a LS-associated cancer is/are not available for a genetic assessment/testing, then a close unaffected relative may be considered for assessment. Be sure to provide as much information as possible on the referral including how individuals are related and who is deceased.

Because clinical criteria for identifying individuals with LS have suboptimal sensitivity, automatic tumour screening is recommended.1,2

Tumour screening

Mismatch Repair Deficiency

Mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency testing is recommended for tumours from all individuals with newly diagnosed colorectal and endometrial cancers, as well as ovarian, gastric, gastroesophageal junction, small bowel, ureter, renal pelvis, hepatobiliary and glioblastoma cancers, regardless of age.1 MMR deficiency may be determined by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of the tumour to examine expression of the proteins coded by the four MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2).

Microsatellite Instability

Lynch syndrome can be characterized by tumours that exhibit microsatellite instability (MSI). A microsatellite is an area of DNA with a repetitive sequence (i.e. CGCGCGCGC or GAAGAAGAA). These stretches of DNA are susceptible to changes in the number of repeats when a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant in an MMR gene is present. Cancer arising as the result of a defective MMR gene often exhibits an inconsistent number of microsatellite repeats when compared to normal tissue - this is called microsatellite instability (MSI). Approximately 90% of LS-associated tumours occurring in individuals with Lynch syndrome exhibit MSI.2 Approximately 15% of sporadic colorectal cancers (not associated with LS) also exhibit MSI.9

A recently published Canadian consensus statement1 recommends universal reflex (automatic) MMR deficiency testing by IHC or MSI testing on all invasive colorectal and endometrial cancers as well as all ovarian, gastric, gastroesophageal junction, small bowel, ureter, renal pelvis, hepatobiliary and glioblastoma cancers, regardless of age. Greater than 90% of LS tumours will be detected by these methods.2 Following a positive result on MMR or MSI testing, the individual can be offered genetic testing by a multigene panel which includes at least all five LS-associated genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM). Additional tumour analysis may be considered based on the MMR deficiency results, the tumour type and/or family history.1,2 Reflex tumour testing currently varies across Canada, although many provinces have implemented this recommendation for colorectal and endometrial cancers.

Private pay genetic testing

Some individuals may wish to pay out of pocket for genetic testing, for example if they do not qualify by provincial criteria. Generally, this testing will not be arranged by genetic centres but may be requested of primary care practitioners. Several companies offer genetic testing for hereditary cancer predispositions. When choosing a genetic testing company, consider whether:

- The genetic testing laboratory and clinical personnel are accredited/certified by appropriate governing bodies (e.g. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certification or appropriate provincial licensure bodies for laboratories, board-certification of genetic counsellors and geneticists).

- Pre- and post-test genetic counselling is offered and delivered by a qualified and certified health professional (e.g. Canadian Board of Genetic Counselling, American Board of Genetic Counseling).

- Testing analyses the whole gene (full sequencing) (preferred) or targets genetic variants more common in specific populations e.g. ancestry-based screening (not ideal for most people)

- The gene panel includes testing for the genetic condition suspicious in the family, i.e. how comprehensive is the panel

- The results will be actionable. Not every gene offered on a gene panel necessarily has evidence-based guidelines for surveillance, which can lead to uncertainty.

- Privacy of genetic information is ensured and how that is achieved. Some companies leverage genetic and personal information, allowing third-party access by entities such as research projects, advertising, law enforcement or pharmaceutical companies.

- The testing is performed within Canada or whether the sample is sent out of country, where legislation around genetic testing, privacy etc. may be different.

It is also important to keep in mind that a negative result, although reassuring, may not rule out the familial condition without confirmation that the patient’s testing included analysis of the known familial variant. Additionally, a negative result does not mean the patient is not at increased risk for cancer. Risk assessment and screening recommendations are still based on family and personal health history. See more in What do the genetic test results mean?

What do the genetic test results mean?

For more information on genomic testing and results see our point of care tool. Most provincial genomic laboratories and clinics will have board-certified genetic counsellors available to answer your questions about genetic test results and are happy to take your calls.

Affected individuals (have/had cancer diagnosis)

Positive result: A pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) variant in a cancer predisposition gene was identified. If the gene is associated with the person’s cancer diagnosis, this explains their cancer. Results may be used by oncology to inform treatment and/or surveillance plan and may allow for access to new effective therapies. The individual is likely at higher risk for subsequent cancer diagnoses. Additional screening and surveillance for other cancers may be indicated. First degree relatives (parents, siblings, offspring) have a 50% chance to inherit this gene variant and to also be at risk. Relatives can have genetic testing for this familial variant.

Negative/uninformative result: No variants of clinical significance were identified in any of the genes on the cancer panel. Given the comprehensiveness of cancer gene panels, a negative result significantly reduces the likelihood of a hereditary cancer condition in the person tested. Depending on the family history, other relatives may still be eligible for genetic testing. Screening and surveillance recommendations for the individual and their relatives will be based on personal and family history.

Variant of uncertain significance (VUS): A variant in a gene was identified but its significance is not yet known. The laboratory cannot confidently determine if the gene variant identified is pathogenic or benign, as available evidence is insufficient or conflicting. This result is reassuring as pathogenic variants in high/moderate risk cancer genes have been ruled out, however a hereditary cancer condition cannot be completely excluded. A board-certified genetic counsellor or a geneticist can help to interpret the laboratory report. No changes to medical management are indicated. Family members are typically not offered genetic testing for a VUS. Clinics and laboratories differ in their re-contact protocols, but generally a patient would be encouraged to re-contact their genetics provider in 3-5 years for updates on re-classification of the VUS they carry. Re-classification of a VUS could mean the variant is now determined to be pathogenic or more often, benign.

Unaffected individuals (never had a cancer diagnosis)

Positive result: A P/LP variant in a cancer predisposition gene was identified.

The individual is at increased risk for cancers associated with the gene. Screening and medical management recommendations can be made based on the combination of genetic test result and family history. First degree relatives (parents, siblings, offspring) have a 50% chance to inherit this gene variant and to also be at risk. Relatives can have genetic testing for this familial variant.

Negative result:

True negative: The familial variant was not detected.

This is where a P/LP variant in a cancer predisposition gene has already been identified in a relative. Testing was solely to detect the presence or absence of the familial pathogenic variant. This individual is not at increased risk for cancer. Depending on the family history, population-based cancer screening is still recommended.

Uninformative: No variants of clinical significance were identified in any of the genes on the cancer panel.

Given the comprehensiveness of cancer gene panels, a negative result significantly reduces the likelihood of a hereditary cancer condition in the person tested, however without confirmation of a gene variant responsible for the family’s cancer, this is uninformative. Screening and surveillance recommendations for the individual and their relatives will be based on personal and family history. Depending on the family history, other relatives may still be eligible for genetic testing.

Variant of uncertain significance (VUS): A variant in a gene was identified, but its significance is not yet known. The laboratory cannot confidently determine if the gene variant identified is pathogenic or benign, as available evidence is insufficient or conflicting. A board-certified genetic counsellor or a geneticist can help to interpret the laboratory report. No changes to screening or medical management are indicated. Family members are typically not offered genetic testing for a VUS. Clinics and laboratories differ in their re-contact protocols, but generally a patient would be encouraged to re-contact their genetics provider in 2-5 years for updates on re-classification of the VUS they carry. Re-classification of a VUS could mean the variant is now determined to be pathogenic or benign.

NOTE: In some genes, when two P/LP variants are inherited, one from each parent, this can result in a serious clinical presentation with high cancer risk and childhood onset (e.g. PMS2/PMS2 results in constitutional mismatch repair deficiency which can result in child-onset cancers). If there is suspicion of a hereditary cancer predisposition in the partner of a carrier of a LS-gene P/LP variant or known consanguinity, consider genetic counselling for the couple.

A word about Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS): A VUS is a result that leaves ambiguity for a patient and, depending on a patient’s experience with cancer (personal and family), attitudes toward healthcare and education level, there may be an inappropriate expectation of increased monitoring based on the result.4 Discussions with healthcare practitioners are important in shaping a patient’s understanding of the result, managing uncertainty and setting expectations.10 It is also important to note that the rate of VUS is reported to be significantly higher in those of non-European ancestry (e.g. Hispanic, African, Asian and Pacific Islander). This has to do with the lack of diversity in clinical and research contexts and the under-representation of non-European groups in genomic databases that are used for interpretation by laboratories.9 The majority of VUSs in hereditary cancer risk genes will eventually be classified as benign.

Genetic testing of children and minors11,12

Guidelines recommend that, unless there is evidence for timely medical benefit or actionable management in the pediatric period, genetic testing for adult-onset conditions should be deferred until the child/minor is capable of deciding whether to be tested. Clinicians are not obligated to comply with requests from parents to test healthy children. There may be exceptions, such as where the wait for testing itself may cause an undue psychological burden for the child. Requests for testing by competent, well-informed adolescents may be considered in conjunction with comprehensive genetic counselling.

What are the benefits and considerations of genetic testing?

Benefits:

- A positive result can explain why a person developed cancer and confirm a hereditary predisposition in the family

- Oncology may use the result to inform treatment

- Additional surveillance, medical and/or surgical recommendations may be suggested

- Clinical intervention for those with known hereditary cancer predispositions can improve outcomes12

- Relatives can have genetic testing for the familial variant

- At-risk relatives can be identified and other relatives without the familial variant can be reassured. Both can be given more accurate risk assessments1 and management plans

- Positive health behaviours can be reinforced1

Considerations:

- Some may experience psychological distress over:

- the increased risk to develop cancer

- the possibility of passing an increased cancer risk to offspring

- the uncertainty of a negative result or a variant of uncertain significance

- the uncertain likelihood of a cancer diagnosis, as not everyone with a genetic predisposition will develop cancer

- Family issues such as confidentiality concerns or estrangement may inhibit the transfer of information between relatives

- In Canada, the Genetic Non-Discrimination Act (GNA) became law in 2017. This law protects Canadians and their genomic information. Some key points of the law are that GNA prohibits:14

- Discrimination based on genomic characteristics

- Providers of goods and services (including insurance) from:

- requesting or requiring a genomic test

- requesting or requiring the disclosure of genomic test results either past or future

- Federally regulated employers from using genomic test results in decisions about hiring, firing, job assignments, or promotions

Gene-specific cancer surveillance and management recommendations

A multidisciplinary approach involving medical, surgical, and genetic specialties is the best approach to managing those with a hereditary cancer predisposition.1 Consider a referral to a genetics specialist if not already arranged to ensure the patient receives appropriate counselling regarding their hereditary condition. If your patient had genetic counselling several years ago, consider reaching out to your local genetics specialist by phone or eConsult to inquire about any updated screening recommendations, as they evolve over time.

For those currently under the care of oncology: the oncologist will likely recommend screening and surveillance related to the current cancer diagnosis. Because those with hereditary cancer predispositions often have increased lifetime risk for additional cancers, management of those risks may be appropriate after treatment of the current cancer or may be combined with treatment for a current cancer.

Screening and Cancer risk reduction

All screening should be offered with a discussion of the benefits (such as early detection and reduced mortality) as well as the risks and limitations of screening (such as increased chances for false positive results and follow-up).

Individuals with LS are encouraged to have yearly visits with their primary care practitioner and not ignore any unusual changes to their health status, particularly any bowel or stomach problems, unexpected bleeding, neurologic or skin changes.

Note: Individuals who have a first-degree relative with LS with a confirmed genetic variant, but decline genetic testing for themselves, should follow the screening recommendations below i.e. be treated as if they have LS until a negative genetic test result is confirmed.

Colorectal

Screening2

MLH1/MSH2/EPCAM: Colonoscopy starting at age 20–25 years. If the youngest CRC diagnosis is younger than 25 years, begin screening by colonoscopy 2–5 years prior to the earliest CRC. Repeat every 1–2 years.

PMS2/MSH6: Colonoscopy starting at age 30–35 y. If the youngest CRC diagnosis is younger than 30 years, begin screening 2–5 years prior to the earliest CRC diagnosis. Repeat every 1–3 years.

Cancer risk reduction

The Canadian consensus statement recommends considering the use of daily aspirin, at a minimum dose of 81mg, to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer.1 A double-blind randomized controlled study that looked at the use of 600mg of aspirin daily for 2 years by individuals with LS found a significant decrease in the likelihood of CRC with no significant increased likelihood of adverse events.15 The cancer risk reduction effect was seen to last for 10 years but did not become apparent until 5 years after starting aspirin.15 The exact dosage and duration are still being studied, and these should be determined on an individual basis.1,2Discussions about the benefits and contraindications of aspirin use are important.1

Endometrial2

Screening

Screening is generally not recommended as there is little evidence to support it reduces morbidity and mortality in those with LS. Those assigned female at birth can be educated about the signs and symptoms of endometrial cancer (e.g. abnormal uterine bleeding) and be encouraged to promptly seek medical attention if present.

Cancer risk reduction

The timing of a total hysterectomy can be tailored to each patient, taking into account factors such as completion of childbearing, existing medical conditions, family history, and the specific Lynch syndrome gene involved.

MLH1/MSH2/EPCAM/MSH6: Hysterectomy may be considered starting at age 40.

PMS2: Hysterectomy may be considered starting at age 50.

Ovarian2

Screening

Screening is generally not recommended as there is little evidence to support it reduces morbidity and mortality. Those assigned female at birth can be educated about the signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer and be encouraged to promptly seek medical attention if present.

Cancer risk reduction

Risk reduction bilateral oophorectomy (RRBSO) may reduce the incidence of ovarian cancer. The timing of a RRBSO should be tailored to each patient, taking into account factors such as completion of childbearing, existing medical conditions, family history, and the specific Lynch syndrome gene involved.

Since oophorectomy-induced early menopause can negatively impact bone density, heart health, and overall quality of life, the use of estrogen replacement therapy can be considered.

MLH1/MSH2/EPCAM: RRBSO may be considered starting at age 40.

MSH6: Opportunistic salpingectomy may be considered starting at age 40, with delayed bilateral oophorectomy starting at age 50.

PMS2: BSO may be considered starting at age 50.

Upper gastrointestinal2

Screening

MLH1/MSH2/EPCAM/MSH6/PMS2: Consider upper endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy) starting at age 30–40 and repeat every 2–4 years. Consider earlier based on family history.

Urothelial (renal pelvis, ureter, and/or bladder)2

Screening

There are no clear evidence-based screening recommendations for urothelial cancers in those with LS. For those with a family history of urothelial cancer, consider annual urinalysis for cytology starting at age 30–35. Individuals with P/LP variants in MSH2/EPCAM appear to be at a higher lifetime risk than those with other LS-associated gene variants.

Additional cancer2

Screening for other cancers (e.g. pancreas, breast) would be based on personal and family history.

References

- Aronson M, Palma L, Semotiuk K, et al. Canadian consensus for the assessment and testing of Lynch syndrome. J Med Genet. 2025 Apr 17;62(5):326-334

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal, Endometrial, and Gastric Version 4.2024 — April 2, 2025 NCCN.org. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_ceg.pdf [Accessed July 2025]

- Abu-Ghazaleh N, Kaushik V, Gorelik A, et al. Worldwide prevalence of Lynch syndrome in patients with colorectal cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Genet Med. 2022 May;24(5):971-985

- Williams MH, Hadjinicolaou AV, Norton BC, Kader R, Lovat LB. Lynch syndrome: from detection to treatment. Front Oncol. 2023 May 1;13:1166238.

- Lackman MJ, Wilkinson AN. Colon cancer in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2024 Jan;70(1):33-37

- Canadian Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Statistics. https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/colorectal/statistics#:~:text=It%20is%20estimated%20that%20about,43%20will%20die%20from%20it. [Accessed July 2025]

- Xie L, Semenciw R, Mery L. Cancer incidence in Canada: trends and projections (1983-2032). Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2015 Spring;35 Suppl 1:2-186. English, French.

- Ahsan MD, Levi SR, Webster EM, et al. Do people with hereditary cancer syndromes inform their at-risk relatives? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PEC Innov. 2023 Feb 17;2:100138.

- Ndugga-Kabuye MK, Issaka RB. Inequities in multi-gene hereditary cancer testing: lower diagnostic yield and higher VUS rate in individuals who identify as Hispanic, African or Asian and Pacific Islander as compared to European. Fam Cancer. 2019 Oct;18(4):465-469.

- Mighton C, Clausen M, Shickh S, Baxter NN, Scheer A, Sebastian A, Muir SM, Kim THM, Glogowski E, Schrader KA, Regier DA, Kim RH, Lerner-Ellis J, Bayoumi AM, Thorpe KE, Bombard Y. How do members of the public expect to use variants of uncertain significance in their health care? A population-based survey. Genet Med. 2023 May;25(5):100819.

- Moore AM, Richer J. Genetic testing and screening in children. Paediatr Child Health. 2022 Jul 18;27(4):243-253. PMID: 35859684

- Committee on Bioethics; Committee on Genetics and; American College of Medical Geneticists and; Genomics Social; Ethical; Legal Issues Committee. Ethical and policy issues in genetic testing and screening of children. Pediatrics. 2013 Mar;131(3):620-2. PMID: 23428972.

- Dinh TA, Rosner BI, Atwood JC, Boland CR, Syngal S, Vasen HF, Gruber SB, Burt RW. Health benefits and cost-effectiveness of primary genetic screening for Lynch syndrome in the general population. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011 Jan;4(1):9-22.

- Cowan JS, Kagedan BL, Graham GE, et al. Health care implications of the Genetic Non-Discrimination Act: Protection for Canadians' genetic information. Can Fam Physician. 2022;68(9):643-646

- Burn J, Sheth H, Elliott F, et al. Cancer prevention with aspirin in hereditary colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome), 10-year follow-up and registry-based 20-year data in the CAPP2 study: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020 Jun 13;395(10240):1855-1863

Additional Resources for Clinicians and the Public

- Colorectal Cancer Canada

- Lynch Syndrome International

- FORCE (Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered)

- Alive and Kickn'

Authors: S Morrison MS CGC, JE Allanson MD FRCPC, S Walji MD CCFP, A Rusnak MD FRCPC, M Aronson MS CCGC CGC, JC Carroll MD CCFP

Disclaimer:

· GECKO is an independent not-for-profit program that does not accept support from commercial or non-academic entities.

· GECKO aims to aid the practicing non-genetics clinician by providing informed resources regarding genetic/genomic conditions, services and technologies that have been developed in a rigorous and evidence-based manner with periodic updating. The content on the GECKO site is for educational purposes only. No resource should be used as a substitute for clinical judgement. GECKO assumes no responsibility or liability resulting from the use of information contained herein.

· All clinicians using this site are encouraged to consult local genetics clinics, medical geneticists, or specialists for clarification of questions that arise relating to specific patient problems.

· All patients should seek the advice of their own physician or other qualified clinician regarding any medical questions or conditions.

· External links are selected and reviewed at the time a page is published. However, GECKO is not responsible for the content of external websites. The inclusion of a link to an external website from GECKO should not be understood to be an endorsement of that website or the site’s owners (or their products/services).

· We strive to provide accurate, timely, unbiased, and up-to-date information on this site, and make every attempt to ensure the integrity of the site. However, it is possible that the information contained here may contain inaccuracies or errors for which neither GECKO nor its funding agencies assume responsibility.