Download the PDF here

Schizophrenia may be isolated or associated with physical and/or learning differences (syndromic).

Isolated schizophrenia has complex inheritance. There are many potential susceptibility genes and genomic regions under investigation. Development of disease likely depends on the interaction of genetic susceptibility and other factors. Although empiric risks for relatives to develop schizophrenia exist, no clinical genetic test is currently available. Genetic counselling is an option for affected individuals and those with a family history of schizophrenia.

About 1-2% of individuals with schizophrenia have a syndrome caused by a subtle chromosome abnormality called 22q11 deletion. Individuals with schizophrenia and a history of congenital anomalies such as cleft palate or heart defects, and/or speech/learning difficulties, should be offered genetics referral for evaluation for 22q11 deletion syndrome. Genetic counselling and testing may lead to specific management plans for affected individuals and may facilitate reproductive planning decisions for families.

Updated July 2019

What is schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia is diagnosed in about 1% of the population; males and females are equally affected. Onset is typically in the early 20s in males and late 20s in females. Early symptoms are social withdrawal, loss of previous interests, unusual thinking/behaviour, deterioration of hygiene/grooming, depression, irritability, anxiety and sleep disturbances. Late symptoms are hallucinations, delusions and disorganized behaviour, decrease in emotional range, poverty of speech, loss of interest and lack of drive. Cognitive symptoms are deficits in attention and executive functions like organization & abstract thinking. Treatment includes anti-psychotics such as haloperidol, risperidone, and olanzapine, and supportive therapy.1

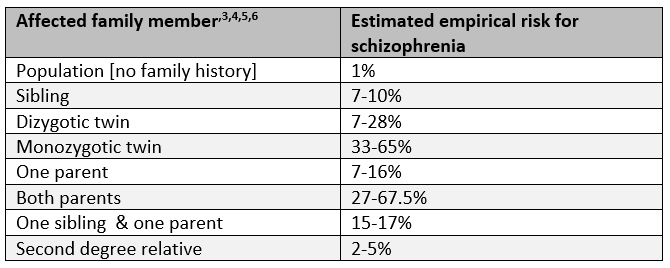

Heritability of schizophrenia is high (60-80%). First-degree relatives (children, parents or siblings) of an affected individual have about a 10-fold increased risk of developing schizophrenia or schizophrenia spectrum disorders (schizotypal personality disorder, paranoid personality disorder, schizoaffective disorder, unipolar/major depression) – see Table 1. No single gene is known to contribute a major risk for schizophrenia. Genetic studies suggest multiple genes and/or genomic regions, each making a small contribution to the risk of schizophrenia. The accumulation of genetic susceptibility factors plus other environmental, developmental and epigenetic factors lead to disease. Many potential susceptibility genes and genetic regions have been identified, including small chromosome duplications, deletions and copy number variants. More studies are needed to determine how these genomic regions interact with other factors to contribute to an individual’s risk to develop schizophrenia.2 Because of the stigma of psychiatric illness some individuals may be unwilling to discuss or unaware of their family history. There are few data on the risk for psychiatric illness where multiple family members are affected.3

Table 1. Estimated empirical risk for schizophrenia based on family history.

Red Flags to consider genetic testing or genetic consultation

If an individual with schizophrenia has other health problems (such as a history of congenital anomalies, learning or speech difficulties), consider referring to a genetics clinic for an evaluation for 22q11 deletion syndrome (also known as velocardiofacial syndrome or DiGeorge syndrome). Only 1-2% of individuals with schizophrenia are estimated to have 22q11 deletion syndrome. 22q11 deletion syndrome has variable features, including a subtle yet characteristic facial appearance, physical defects (heart, palate), endocrine disorders (hypocalcaemia, hypothyroidism), speech (hypernasal) and learning difficulties. Approximately 25% of individuals with 22q11 deletion syndrome develop schizophrenia and about half have other psychiatric illnesses including attention deficit disorder, autism spectrum disorder, general anxiety and mood disorders. Genetic testing (microarray, fluorescent in situ hybridization [FISH]) will detect ~95% of cases. Identification of the 22q11 deletion facilitates more specific anticipatory guidance and management. Many individuals with this syndrome have unrecognized health problems, for example, seizures may not be recognized as a symptom of hypocalcemia, recurrent infections may be caused by immune deficiency, or an unrecognized cardiac structural defect may exist. Families with an affected individual may also want genetic testing or counselling for family planning purposes.7

Although there is no genetic testing for isolated (non-syndromic) schizophrenia, genetic counselling may offer the following benefits:8

- Provision of empiric recurrence risks to family members which can help with adjustment to personal risk and family planning (see Table 1)

- Education of family members about psychiatric illness

- Identification of the rare syndromic cause of schizophrenia

What does the genetic test result mean?

Genetic testing is not available or routinely recommended for isolated schizophrenia. Testing for the susceptibility genes/genomic regions for schizophrenia has no clinical utility until it is determined how these genes/genomic regions modify an individual’s risk of developing schizophrenia.9 Be wary of direct-to-consumer marketing of genetic tests for psychiatric illness. The clinical utility of these tests has not been established.

Confirmation of the 22q11 deletion in an individual with schizophrenia allows the physician to plan evaluations looking for associated medical problems5. Close relatives may want to have testing to determine if the deletion is de novo or familial. The affected individual can use this information for family planning and prenatal diagnostic purposes.

For a review article on schizophrenia see Rethelyi JM et al., Genes and environments in schizophrenia: The different pieces of a manifold puzzle. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013; 37(10)Part 1: 2424-2437.

Click here to connect to your local genetics centre.

References

[1] Schultz SH, North SW, Shields CG. Schizophrenia: A review. Am Fam Physician. 2007; 75:1821-1829.

[2] Giegling I, Hosak L, Mossner R, Serretti A, Bellivier F, Claes S et al. Genetics of schizophrenia: A consensus paper of the WFSBP Task Force on Genetics. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2017; 18(7): 492-505.

[3] Austin JC, Peay HC. Applications and limitations of empiric data in provision of recurrence risks for schizophrenia: a practical review for healthcare professionals providing clinical psychiatric genetics consultations. Clin Genet. 2006; 70; 177-187.

[4] Cardno AG, Gottesman II. Twin studies of schizophrenia: from bow-and-arrow concordances to Star Wars MX and functional genomics. Am J Med Genet. 2010; 97:12-17.

[5] Hilker R, Helenius D, Fagerlund B, Skytthe A, Christensen K, Werge TM et al. Heritability of schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum based on the nationwide Danish Twin Register. Biol Psychiatry. 2017; 83:492-498.

[6] Gottesman II, Laursen TM, PhD, Bertelsen A, Mortensen PB. Severe mental disorders in offspring

with 2 psychiatrically ill parents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010; 67(3): 252-257.

[7] McDonald-McGinn DM, Emanuel BS, Zackai EH. 22q11 Deletion Syndrome [Internet]. Seattle (WA): GeneReviews® (US); c1993-2019 [updated 2013 Feb 23; cited 2019 July 12]. Available from:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1523/

[8] Moldovan R, Pintea S, Austin J. The efficacy of genetic counseling for psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. J Genet Counsel. 2017; 26:1341-1347.

[9] Mitchell PB, Meiser B, Wilde A, et al. Predictive and diagnostic genetic testing in psychiatry. Clin Lab Med. 2010; 30(4):829-46.

Other resources: The Schizophrenia Society of Canada http://www.schizophrenia.ca/

Authors: AL Rideout MS (C)CGC, JE Allanson MD FRCPC, S Morrison MS CGC and JC Carroll MD CCFP

Updated by the GECKO team: S Yusuf MS C, JE Allanson MD FRCPC, and JC Carroll MD CCFP

Disclaimer:

· GECKO is an independent not-for-profit program that does not accept support from commercial or non-academic entities.

· GECKO aims to aid the practicing non-genetics clinician by providing informed resources regarding genetic/genomic conditions, services and technologies that have been developed in a rigorous and evidence-based manner with periodic updating. The content on the GECKO site is for educational purposes only. No resource should be used as a substitute for clinical judgement. GECKO assumes no responsibility or liability resulting from the use of information contained herein.

· All clinicians using this site are encouraged to consult local genetics clinics, medical geneticists, or specialists for clarification of questions that arise relating to specific patient problems.

· All patients should seek the advice of their own physician or other qualified clinician regarding any medical questions or conditions.

· External links are selected and reviewed at the time a page is published. However, GECKO is not responsible for the content of external websites. The inclusion of a link to an external website from GECKO should not be understood to be an endorsement of that website or the site’s owners (or their products/services).

· We strive to provide accurate, timely, unbiased, and up-to-date information on this site, and make every attempt to ensure the integrity of the site. However, it is possible that the information contained here may contain inaccuracies or errors for which neither GECKO nor its funding agencies assume responsibility.